midwest opulence

mancini, a lot of drinks, good sweaters

We don’t normally eat in the dining room. It’s tucked away with the rest of the antiques: a master copy painting procured from Poland depicting Roma musicians and a woman dancing, wedding china and uranium-laden glassware in an ancient barrister bookcase, a handmade red tablecloth atop the dark wood table that has been graced with many Thanksgiving and Christmas dinners. These days I spend a lot of time in the dining room among the old and holy heirlooms, sitting at the big table by the bay window, working, diligently and not diligently, attuned to the chatter from the TV drifting in and the bustling in the kitchen on the other side of the wall. My parent’s home is a modest one, with low ceilings and little 70s flourishes, like wood trim throughout. It is profoundly safe and when I am here, I feel forgotten by time.

It gets dark around 5:30. I’m having a little thimble of Cloosterbitter, which is striking, green, and bitter, a liqueur made with nettles, cloverleaf, daisies, mint, dandelion — some liveliness, you realize, bolsters you against the winter scenery. It doesn’t even really snow much in Minnesota anymore, not like it did when I was a kid. When it does, the sun reflects off the white and illuminates everything. You remember in this blinding light that summer exists. Without the snow, the sky is persistently gray, and the earth is exposed in its death. I am managing this depression with little cans of Coca Cola and trips to the sauna. I lack true midwestern hardiness. I do complain about the cold, meaning I’m NGMI. There is a yin-yang element to the flaxen nordic cheer of Minnesotans — the opposite but interconnected, mutually perpetuating force behind it is something called Sisu, a Finnish term for “suck it up, buttercup.”

My mom the other day played Henry Mancini on the speakers, which is the easy-listening her parents, my grandparents, would put on the turntable. It’s atmospheric, it’s swanky. I hear Mancini and I’m reminded of the leather chair by the fieldstone fireplace in their Wisconsin home. At times I do want to live in the kind of world my grandparents created — stiff Manhattans in the evening, a clean kitchen under the gaze of a framed portrait of JFK, embers glowing in the fire, duck hunting on the weekend. I wonder sometimes if I have spent my life dreaming about the wrong things and if the path ahead of me wasn’t the right path, all along. If, instead, I should become a midwest party girl, marry, travel, wear Ralph Lauren, know my way around a cocktail bar.

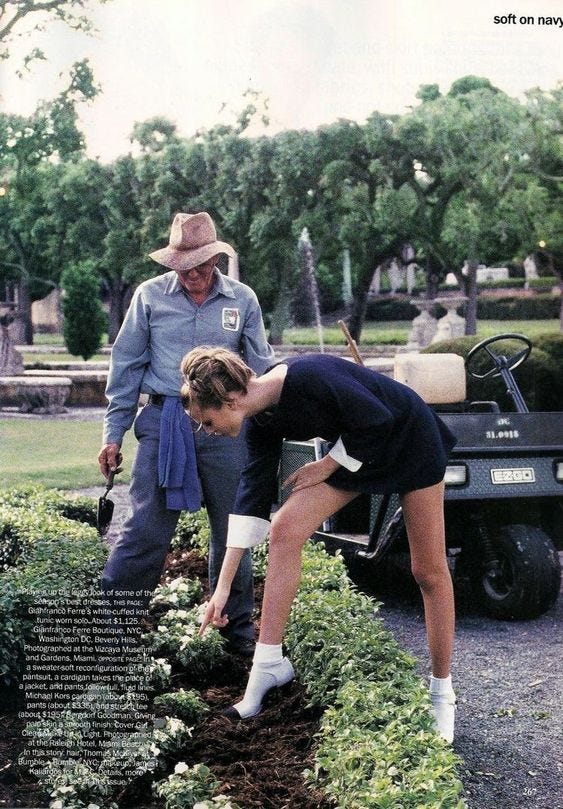

There are charming things about being home. Sometimes it is the memories. And I do like running errands in the suburbs. Out and about, I exchange a kindly smile with a well-dressed business man headed on his way out. He’s wearing a wool overcoat and holds the door for me. I don’t know what a Branch Manager is, but he carries himself like a Branch Manager. I look at his arms and notice we are both picking up heritage wool sweaters from the dry cleaners. This is what a solid and real person is, I think, compared to my wavering nervousness, typical of someone who doesn’t belong to any one place, who doesn’t know what they want to do, or what they really think. At times what I think will make me happy is to become even more transparent, to sleep on a wood floor, in a city that is warmer, more unforgiving. But the midwest braces me with another version of personhood, of non-anonymity. One that has nothing to do with clout and everything to do with shaping yourself into something. Perhaps a respectable human being like this man.

Over Aviations, and I promise, I have other hobbies now besides drinking, my friend, a homegrown Minnesota boy, tells me about his first trip to New York. Women fawned over him for his midwestern roots. “It’s sort of like I was a Noble Savage,” he says, and we laugh — and I try to explain that dating in a place like New York or Los Angeles is sort of a nightmare because of the gender ratio.

“The assumption is that a midwestern guy will want to marry you and build you a cabin,” I explain, “and what’s funny is that, at least compared to coastal cities, the odds of that happening here are slightly better.”

He’s not convinced people are that different, city to city. I’m sure he’s right.

you really nailed a certain hard to describe feeling i’ve had about home for a while. loved that bit about Branch Manager

💖